1

CHAPTER ONE

BIBLIOLOGY AND CANONIZATION

When it comes to studying the Bible, the first questions to ask are, “Is the Bible worth studying?” and “Is

this the right Bible?” These questions form the heart of Bibliology — the study of the Bible. The

information on which one bases life is an important decision that should be approached with scrutiny. If a

person were to base his or her diet off of what was seen on TV during the Super Bowl, that person’s

physical health would rapidly decline. In this same way, if someone were to form his or her life’s principles

off a few catchy phrases, that person’s mental, physical and spiritual health could all crumble.

The first question, “Is the Bible worth studying?” stems from a person’s view of God. A God who is loving

would likely desire relationship, a vehicle through which His love could flow. This desire for relationship is

proven by the work of Christ. God sent His son to die so that the broken relationship with mankind would

be restored. If God so desires relationship, mankind can assume He has the wisdom to use the tool that

nourishes relationship: communication. The premise just made is illustrated in the following line.

God is love > love requires relationship > relationship requires communication > God

communicates

Having established that God communicates, the next step is to establish our response to it. Simply put, if

God is communicating, are humans listening? If the all-knowing, all-loving God puts forth the effort to

communicate, we would be wise to position ourselves to receive the communique which is the Bible.

From this base, one can assert the Bible is in fact worth studying, assuming the text is correct. As Millard

Erickson writes in Christian Theology, “written record, to the extent that it is an accurate reproduction of

the original revelation, is also by derivation revelation and entitled to be called that.” In essence, Erickson

is saying, “If the text accurately records what God said and did, it has the same importance on paper as it

did when God said or did it.”

So now, the question is whether or not the Bible as it exists today is in fact a good account of what God

has said and done. The answer to this question will be broken into two sections: the canonization of the

Old Testament, and the canonization of the New Testament.

Canonization of the Old Testament

Canonization is the process by which the books of the Bible were discovered as authoritative. Men did not

canonize Scripture; men simply recognized the authority of the books that God inspired.

The foundation of the Old Testament (and the entire Bible) is the Pentateuch. These are the first five

books positioned in the Old Testament. The strongest evidence for the validity of the Pentateuch is the

history and traditions of Israel. These five books were written by Moses at the beginning of Israel’s history

after the Exodus from Egypt. These writings were the “ruling documents” for Israel, rather like the

Constitution is the ruling document for the United States of America. The history and existence of

America validates the Constitution; so too does the history and existence of Israel validate the

Pentateuch. So the issue of the Pentateuch being Moses’ words from God to Israel is no more of a

question than the Constitution being the founding father’s words from their hearts and minds to the

government.

After the Pentateuch comes the Histories and the Poetic/Wisdom literature. These texts were believed to

have been canonized alongside the Pentateuch by the scribe Ezra. Their content can be trusted because

the prophets trusted and used them. The Pentateuch set up the office of the prophets as the mouthpiece

2

of God who faithfully declared the revelation that came from God Himself. If Ezra had erred in his

canonization of scripture, God would have corrected this through the prophets who came after his time.

The writings of the prophets were the last addition to the Old Testament, having been in the canon for

several centuries before the time of Jesus. He puts the final stamp of approval on the Old Testament.

Jesus quoted the Old Testament with frequency and surety indicating His approval of it. Jesus then takes

it one step beyond this in Matthew 22:40 by grouping all the law and the prophets together as a valid

basis on which to hang the two great love commandments. Jesus completely affirms the Old Testament

sections in Luke 24:44.

Canonization of the New Testament

The canonization of the New Testament was built upon the canonization of the Old Testament. When

looking at how the Old Testament was canonized, the councils that decided upon the New Testament

canon pulled out a few key principles (some of which have already been touched on):

● Does this text come with the established weight of approval from those who were around when

it was written?

● Does this text directly refer to God as its authority?

● Does this text fall in line with/build upon the other texts in canon?

The books that comprise what is now the New Testament passed these tests with flying colors. Other

texts may have been considered to have beneficial content, but they were not to be put on the same level

of the Old Testament scriptures. From this step of the canonization process comes one last question: Is

the Bible complete, or shall more scripture be added later? Wayne Grudem in Systematic Theology has

this to say:

The New Testament writings contain the final, authoritative, and sufficient interpretation of

Christ’s work of redemption. The apostles and their close companions report Christ’s words and

deeds and interpret them with absolute divine authority. When they have finished their writing,

there is no more to be added with the same absolute divine authority. Thus, once the writings of

the New Testament apostles and their authorized companions are completed, we have in written

form the final record of everything that God wants us to know about the life, death, and

resurrection of Christ, and its meaning for the lives of believers for all time. Since this is God’s

greatest revelation for mankind, no more is to be expected once this is complete . . The canon is

now closed. (Grudem 64)

The Old Testament contains the accounts of the beginning and the revelations of God leading up to the

time of Christ. Christ is the completion of the revelation of God, and so the accounts regarding Christ and

the clarifying of the Gospel are the completion of the written revelation of God. This is perhaps made

most clear by the presence of the Book of Revelations, which stands with Genesis bookending the whole

body of scripture. Scripture has its beginning, it has its end, and in the middle is the narrative of God’s

love. We have our canon.

The Structure of the Bible

The Bible is comprised of 66 books and is broken down into two testaments, Old and New. The Old

Testament has 39 books, which contain 17 historical books, 5 books of Hebrew poetry, and the 17

prophetic books. The New Testament begins with 5 historical books and has 21 books of doctrine or

teaching and ends with the apocalyptic book of Revelation.

The Pentateuch (which is the first 5 books of the Bible) covers the creation and fall of man, the forming of

the nation of Israel and their journey of being chosen, redeemed, and entering the Promised Land. The

3

remaining 12 books record the conquest of the Land and the development of judges. It continues through

the formation of the kingdom of Israel until the eventual division between Israel and Judah. It then moves

on to the captivities of both kingdoms and the recovery of Judah.

The next 5 poetry books take a step back and do not correspond or relate to the historical books. These

books take an in-depth look at the human heart and condition. Instead of historical experience they deal

with Human experience. These books don’t advance the story of Israel but instead they struggle with

questions of love, wisdom, life suffering, and the character of God. The beautiful thing is that they create

a link that perfectly connects the books of the past to our next section, the prophetic books.

The Old Testament concludes with 17 prophetic books, separated into the Major and Minor Prophets. The

only difference between the two groups is the size of the books. A prophet is simply someone who

speaks for God. In the 17 prophetic books God uses prophets to speak to the nation of Israel and the

surrounding Gentile nations. These books relate to Israel’s spiritual life and their eventual captivity. In

them God communicates with the prophets through dreams, visions, nature, miracles, and his audible

voice. They were used to correct peoples sins, warn them of coming judgment and finally of the coming

Messiah.

The New Testament is a continuation of the Old Testament. There is a 400-year period of silence

between the Old and New Testament. The New Testament begins with the four historical books called the

Gospels. The Gospels, Matthew, Mark, Luke and John, relive the life and ministry of Jesus. They retell all

the wonderful work and miracles of our Savior. Each one ends with Jesus’ crucifixion and resurrection.

They are followed by the book of Acts, which tells of the coming of the Holy Spirit and the forming of the

church. The next section of the New Testament consists of 21 epistles or doctrinal books which are letters

of doctrine that teach truth and active lifestyle. The final book in the Bible is Revelation, a prophetic book

telling of the return of Jesus and the events of the end of the world.

How We Got the English Text

Creation of Ancient texts

A. Communication: how communication took place in the ancient world

Verbal communication (Person to Person)

Story telling within communities

Ancient forms of writing

Scribal writing

Earliest form of hand written documentation

B. Writers: the ones who produced the ancient documents

Scribes

Prophets

God’s own hand

C. Media: the material on which the ancient texts were formed

Papyrus- a paper like substance made from plants

Parchment

Slabs of clay

Wood

Metal

Wax

4

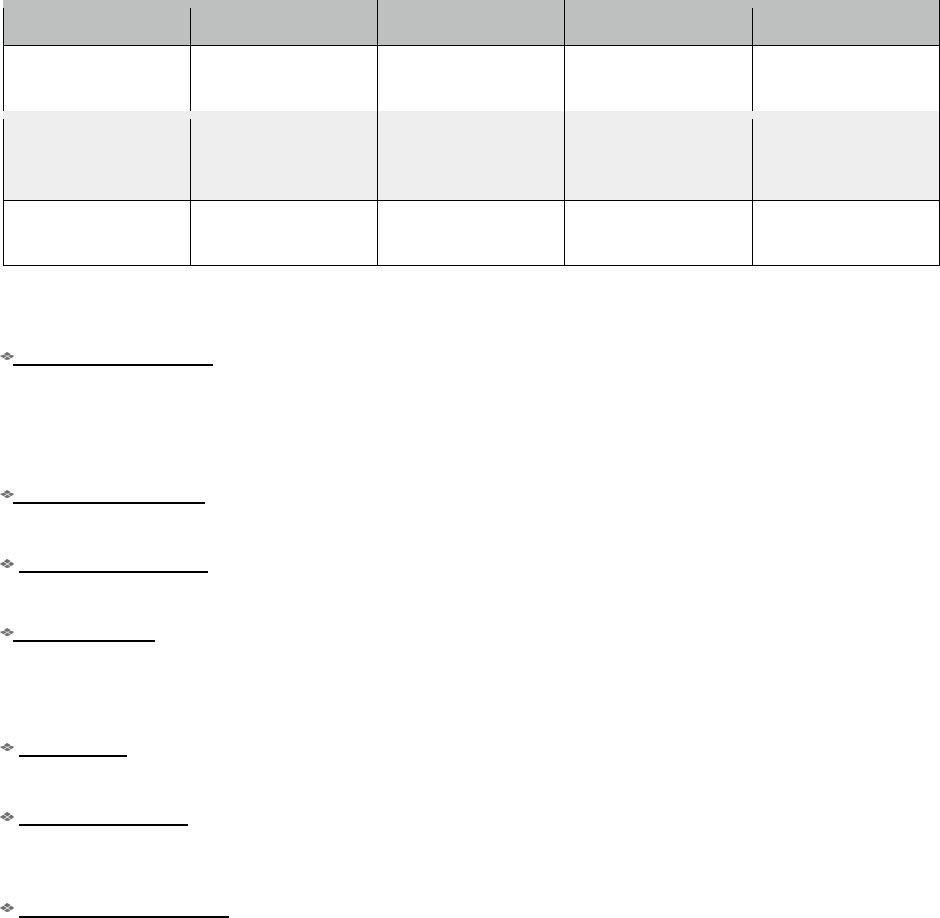

Eras of Bible Translation

300-0 BC

0-400 AD

600-1000 AD

1300-1900 AD

1900-

LXX- 280 BC

(Septuagint)

Codex Sinaiticus-

325 BC

Massoretic Text-

600-1000 AD

English Bibles

Modern English

Bibles

Dead Sea Scrolls

Codex Vaticanus-

325-340 BC

Byzantine Texts

Latin vulgate- 404

BC

Definitions for the previous chart:

The Dead Sea Scrolls or the Qumran Caves Scrolls, are a collection of some 981 different texts

discovered between 1946 and 1956 in eleven caves at the ancient settlement at Khirbet Qumran in the

West Bank. The caves are located about 2 kilometers inland from the northwest shore of the Dead Sea,

from which they derive their name.

The Codex Vaticanus is one of the oldest extant manuscripts of the Greek Bible (Old and New

Testaments).

The Codex Sinaiticus or the "Sinai Bible", is one of the four great uncial codices, an ancient,

handwritten copy of the Greek Bible.

[1]

The codex is a celebrated historical treasure.

The Septuagint is a translation of the Hebrew Bible and some related texts into Greek. Known as the

primary Greek translation of the Old Testament, it is commonly referred to as the Greek Old Testament.

This translation is quoted a number of times in the New Testament,

[1][2]

particularly in Pauline epistles,

[3]

and also by the Apostolic Fathers and the later Greek Church Fathers.

The Vulgate is a late fourth-century A.D. Latin translation of the Bible that became the Catholic

Church's officially promulgated Latin version of the Bible during the 16th century.

The Masoretic

Text is the authoritative Hebrew and Aramaic text of the Tanakh for Rabbinic Judaism.

However, contemporary scholars seeking to understand the history of the Hebrew Bible’s text use a

range of other sources.

The Byzantine text-type is one of several text-types used in textual criticism to describe the textual

character of Greek New Testament manuscripts. It is the form found in the largest number of surviving

manuscripts. It may also be referred as the Majority Text, Traditional Text, Syrian Text, Antiochian or

Ecclesiastical Text.

5

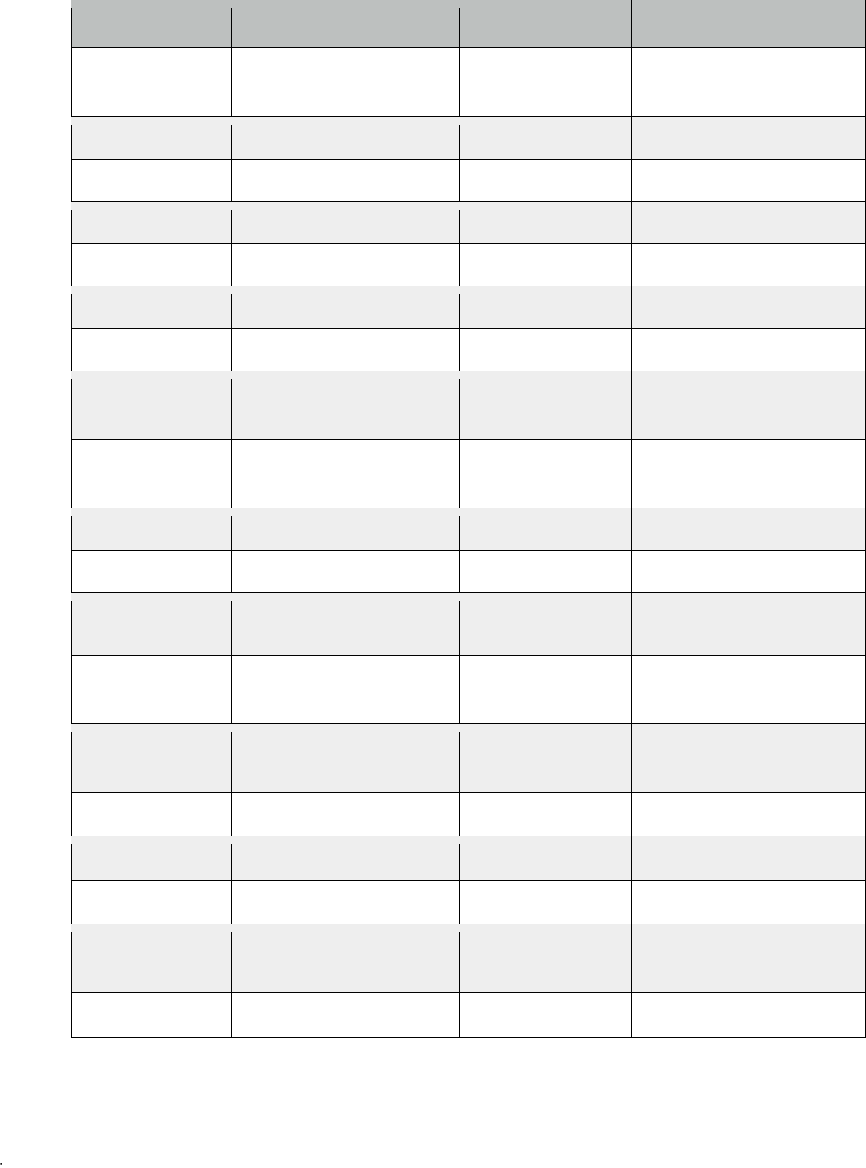

English Bible Translations

Date

Name

Date

Name

900-1300

Glosses, Partials

1971

Living

1379

Wycliffe

1976

Good News Bible

1525

Tyndale (T.N)

1978

New International

1535

Coverdale

1982

New King James

1537

Matthews Bible

1985

New Jerusalem

1539

Great Bible

1987

New Century

1539

Taverners Bible

1990

New Revised Standard

1560

Geneva

1991-95

Contemporary English

Version

1568

Bishops Bible

1993

New International

Readers

1609

Rheim-Doui

1993

Message

1611

King James

1996

New Living

1885

English Revised

Version

2001

New English Translation

1901

American Standard

2001

English Standard

Version

1952

Revised Standard

2002

Today’s New

International

1959

Berkley

1963

Phillip’s (N.T.)

1966

Jerusalem

1970

New American

Standard

1970

New English Bible

Translation Philosophies

There are 3 main approaches to Bible translating:

Formal Equivalence Translating (Correspondence)

6

Dynamic/Functional Equivalence Translating

Paraphrase

Formal Equivalent Translating (FET)

The FET philosophy strives to maintain an exact loyalty to the original Greek and Hebrew texts.

Their motivation is to deliver the original Bible to the English language unchanged.

They try to stay true to the Lexical details (vocabulary) and grammatical structures of the originals.

This technique produces the Word-for-Word translations.

These translations try to find a corresponding English word for each Greek/Hebrew word.

The end result is very accurate, but it can be harder to understand

Theses translations are great for:

Doctrinal and Exegetical study

Theological analysis

Companion texts to Bible dictionaries, concordances, and commentaries.

Dynamic / Functional Equivalent Translations (DET)

This description was originally coined for what was known as “sense-for-sense” translating.

This is where we get our “Thought-for-Thought translations” today.

The primary goal of DET is 2 things:

Present the message of the Bible

Focus on WHAT is God saying, not just how He says it

The question asked by these translators is “Do readers capture what God is saying in the text?”

They are best paired with a word-for-word translation for in-depth study.

These translations seek to express the MEANING of each sentence or paragraph without being tied to

a word-for- word exactness.

They attempt to bridge the gap between yesterday and today’s culture and language.

These translations are good for:

Memorization

Devotional study

Everyday life

Paraphrase Bible Versions

The philosophy behind a paraphrase is to produce a highly readable, simple, and understandable text.

The thought-for-thought translating philosophy has been the spring board for creating paraphrases.

They seek to share the message of the text with a whole new dynamic to it.

These versions seek to present the Heart of God as if the Bible is a personal letter to us today.

The complexity of the Bible is often defused with practical and romantic ideas from these versions.

They can be highly interpretive and poetic.

Paraphrase versions are:

The ultimate devotional tool

Good for learning God’s love and character

Good for the new believers

Good for the unchurched

Good for small groups

Categories of modern English versions of the Bible

The modern versions of the Bible utilize all the translating techniques just mentioned. Put side by side

they form a spectrum that includes the literal translations (formal) on one end and move to the

paraphrases on the other end.

_____________________________________________________________________________

Literal Compound/Hybrid Paraphrase

(Word-for-Word) (Thought-for-Thought)

7

Following are examples of modern versions that fit into these categories.

Word-for-Word Translations:

New American Standard Bible (NASB)

Reading Level: Grade 11

Published: 1971, Updated 1995

The NASB represents a conservative literal approach to Bible translation.

This translation is accurate and readable and is very good for biblical study.

Sample Passage: “For I know the thoughts that I think toward you, saith Jehovah, thoughts of peace, and

not of evil, to give you hope in your latter end” (Jeremiah 29:11)

——————-

English Standard Version (ESV)

Reading level: Grade 7.4

Published: 1951, 2002

The translation committee aimed to produce a Bible good for everyday use as well as for serious

biblical study.

Sample Passage:

“

For I know the plans I have for you, declares the Lord, plans for welfare and not for

evil, to give you a future and a hope.”(Jeremiah 29:11)

—————

New King James Version (NKJV)

Reading Level: Grade 12

Published: 1982

This translation is an attempt to be both faithful to the original languages, as well as to the traditional

King James Version of the Bible.

Sample Passage:

“

For I know the thoughts that I think toward you, says the Lord, thoughts of peace and

not of evil, to give you a future and a hope.” (Jeremiah 29:11)

Reading Level: Grade 4.3

Published: 1995

The goal of this translation was to provide a translation that is both readable and reliable.

Sample Passage: “I know the plans that I have for you, declares the Lord. They are plans for peace and

not disaster, plans to give you a future filled with hope.” (Jeremiah 29:11)

Thought-for-Thought Translations:

New International Version (NIV)

Reading level: Grade 8

Published: 1978, 2011

8

The NIV was created by a team of 100 scholars with the best available Greek and Hebrew manuscripts

on hand.

Their vision statement was: “This translation will be accurate, beautiful, clear and dignified suitable for

reading, teaching, preaching, memorizing, and exegetical use.”

Sample Passage: “For I know the plans I have for you," declares the LORD, "plans to prosper you and not

to harm you, plans to give you hope and a future.” (Jeremiah 29:11)

New Revised Standard Version (NRSV)

Reading Level: Grade 11

Published: 1990

The NRSV is a direct successor or cousin of the King James Version.

Sample Passage:

“

For surely I know the plans I have for you, says the Lord, plans for your welfare and

not for harm, to give you a future with hope.” (Jeremiah 29:11)

________

New Living Translation (NLT)

Reading Level: Grade 6.3

Published: 1996, 2007

The goal of the NLT was to CONVEY THE MEANING of the ancient Hebrew and Greek texts as

accurately as possible to the modern reader

Sample Passage: “For I know the plans I have for you,” says the Lord. “They are plans for good and not

for disaster, to give you a future and a hope.” (Jeremiah 29:11)

Paraphrase Bibles:

New Century Version (NCV)

Reading Level: 6

Published: 1991

The translation committee was composed of the World Bible Translation Center and 50 additional

experienced Bible scholars that also played a part in the NIV, NASB and the NKVJ

Sample Passage: “

I say this because I know what I am planning for you,” says the Lord. “I have good

plans for you, not plans to hurt you. I will give you hope and a good future.”(Jeremiah 29:11)

____________

Living Bible (LB)

Reading level: Grade 8.5

Published: 1971

This version was purposefully kept simple for the modern reader

Sample Passage: “For I know the plans I have for you, says the Lord. They are plans for good and not for

evil, to give you a future and a hope.” (Jeremiah 29:11)

9

——————-

The Message Bible (MB)

Reading level: Grade 5.5-10

Published: 1993, 2001

Sample Passage: “I know what I’m doing. I have it all planned out—plans to take care of you, not

abandon you, plans to give you the future you hope for.” (Jeremiah 29:11)

How To Gain a Basic understanding of the Bible

The Bible is the most important book anyone could ever have in their possession. It surpasses all other

books when it comes to its applicability to the issues of everyday life. Beautifully written, it is woven

together in such a way that it tells the magnificent story of God’s love for mankind.

Attitudes Needed for Studying the Bible

Understanding Scripture and desiring to learn what it says is one of the essential pieces of becoming

more like Jesus. The more one reads about Him through His Word, the more one will know what it’s like

to be truly human the way God designed mankind originally. When one approaches Scripture, it is

required that there be a good attitude toward it. It is only then that what it is saying will be properly

understood (Malmin 3). The following nine attitudes have been adopted from Ken Malmin’s book Bible

Research and should be considered when approaching the Scriptures:

o Attitude of hunger for the Word (Prov. 2:1-11; Ps. 119:20; Matt. 4:4)

o Attitude of love for the Word (Ps. 119:47, 97, 113 — comes from knowing the Author)

o Attitude of enjoyment of the Word (I Pet. 2:2; Eph. 5:26; Jer. 15:16)

o Attitude of respect for the Word (Ps. 119:6, 15)

o Attitude of teachableness (Ps. 119:33-40; Matt. 6:33)

o Attitude of meekness of spirit (James 1:21; Phil. 2:3)

o Attitude of meditation in the Word (Ps. 1:2; Josh. 1:8; Ps. 119:48)

o Attitude of a worshipful spirit (Rev. 4-5)

o Attitude of desiring personal and practical application (The goal of studying the Bible is to

apply the truth to everyday life and to the formation of character.) (Malmin 3)

Awareness of a Communication Gap

When God created humans, He desired to have open fellowship and communication with them. This is

part of the “good” design of creation. Unfortunately, when mankind sinned, a communication gap was

inevitably formed between them and God. It can be observed in Genesis 3 that God still longed for this

open communication when He went searching for Adam and Eve. Yet because of sin, there was a

breakdown between Creature and Creator (Malmin 9). There is good news, however! God chose to

continue to speak to mankind through His written Word. Because of this, there is hope. God has chosen

to communicate in the context of human history so people can relate to and learn from these words, the

same way the Church has for centuries (Fee, Stuart 22).

Observation and Interpretation

There are two primary activities that the student should perform as they work to understand the

Scriptures. One is to gather all the information that a passage has to offer. This is what is called

“observation”. It is the skill of seeing what facts can be discovered by looking carefully at what is said. The

second act takes the gathered facts and works to determine what these facts mean. This is called

“interpretation”. These two activities will be explained more fully below.

Observations: What Does the Text Say?

10

The first step in understanding Scripture is “observation” (Malmin 24). It is important to know what to look

for when first opening up the Bible to study.

It can be easy to read the Bible like any other book, and then walk away and not have a clear

understanding of what it was actually saying. For example, Paul in his epistles to the various churches

used long, run-on sentences that can each be up to a paragraph long! After reading a passage like that, it

can be hard to try and pick out the gist of what he was saying.

The Bible is the inspired, infallible Word of God, and because of this, there is no other book like the Bible.

However, when it comes to analyzing the text of Scripture, it is important to remember that the Bible is to

be read like any other book; it is essential to look for the basic literary patterns (Sproul 63). Nothing will

change the need to read the Bible like literature. The Holy Spirit is the One who reveals the meaning of

Scripture, but to understand what is being said in the various sentences, certain techniques can be used.

What are the things to look for when one reads the Bible? Listed below are nine things to look for when

reading the Bible and gathering information. This list is not exhaustive, as there are other things that can

be mentioned. However, this is a great place to start!

—————

Repetition

Occasionally, an author will repeat a word or phrase in a particular passage. This is his way of drawing

attention to an important point being made. When an author repeats something, it is usually for the sake

of emphasis. He or she wants to highlight something they are saying so their listeners truly recognize the

point of the passage. It is important to note the repeated words, because they often are the main point of

a given passage:

“The elder to the elect lady and her children, whom I love in truth, and not only I, but also all who

know the truth, because of the truth that abides in us and will be with us forever:

Grace, mercy, and peace will be with us, from God the Father and from Jesus Christ the Father’s

Son, in truth and love.” (English Standard Version, II John 1:1-3) (emphasis mine)

It is evident in this passage from Second John that truth is a key element, and it will continue to be

throughout the rest of this short letter. By identifying the repeated words, we are able to get an idea of the

theme in a given passage and get a glimpse of the author’s message.

Verbs

Verbs indicate the ACTION of a passage. They describe what is happening. Verbs also let the reader in

on what the author is commanding, instructing, or encouraging the audience to do. When observing verbs

in a passage, one should take note if the verbs are active or passive, describing activity, or state of being.

Pronouns

In Scripture, there will be many pronouns, especially when reading history or narrative. Some common

pronouns are “her, their, his, I, you, we, them, us, she, he, me,” etc. These are incredibly important

because they indicate who is doing or has done what in a passage. Pronouns also help identify who is

being addressed and who is speaking. Is it a group that’s being instructed? Who is giving the commands?

It is also critical to tie the pronoun back to the name of the person or group that is performing an action,

and identifying that person specifically. Pronouns are only as useful as the people or things to whom they

are tied!

Adjectives

Adjectives can be seen as the flavor in a passage. Adjectives are descriptive. They describe the action

which is being performed, the nature of something being described, or even the type of person who is the

main character of a particular passage. Without adjectives, the color of a passage would be nonexistent,

11

and it would be difficult to distinguish one thing from another. Biblical authors communicate and illustrate

a great deal through adjectives, so they are crucial to note when observing a given passage.

Lists

Biblical authors love to use lists, and they use them in a variety of ways. Sometimes, they exhibit pieces

of something, while other times they are used for the sake of emphasis. Here is an example of the latter.

Matthew 22:37 reads, “And he said to him, ‘You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart

and with all your soul and with all your mind.’” (ESV)

Here, a list is identified: heart, soul, and mind. When looking at this list, the question should be asked,

“Does this list contain pieces of something bigger, or is it restating the same thing with different words for

emphasis?” Questions like these are important in deciphering how a list is used in Scripture. Regardless

of how a list is used, it is a good practice to take note of the things on the list and how they connect with

the other pieces of what the author is saying.

Conjunctions

Words and phrases are often held together by conjunctions. “Although, therefore, then, but, and, or,” etc.

are common conjunctions that can be found in Scripture. Conjunctions serve the purpose of bridging the

gaps between thoughts. Because of the nature of conjunctions, it is important to take note of them, as

they set the flow of the passage. They lead from one section to the next. Conjunctions explain the

structure and help make sense of the thoughts, as well as the order of the thoughts throughout the text.

A good example of a conjunction can be found in Psalm 16:8:

“I have set the Lord always before me;

because he is at my right hand, I shall not be shaken.” (ESV, Psalm 16:8).

The psalmist will not be shaken. Why? Because the Lord is at his right hand. The word “because”

presents the reason for the writer’s confidence. Conjunctions make sense of the words that are put

together, and they are important to note because they add purpose, function, and understanding to the

text.

Comparisons / Contrasts

The Bible is full of comparisons and contrasts. Biblical authors will use them to make a point about two

things that have rich meaning associated with each of them. With comparisons, one particular idea or

event can be paired with a similar one and expounded upon because of those similarities. Here is an

example from Proverbs 17:3:

“The crucible is for silver, and the furnace is for gold,

and the Lord tests hearts.” (ESV, Proverbs 17:3)

The crucible and furnace are used to purify silver and gold, and the comparison is with the Lord, who

purifies human hearts with the same intensity and precision.

Contrasts, in a similar fashion, can display the differences between two or more situations or concepts, all

for the sake of drawing out meaning for the audience to understand. Here is an example of a contrast

from Ephesians 2.

“…among whom we all once lived in the passions of our flesh, carrying out the desires of the

body and the mind, and were by nature children of wrath, like the rest of mankind. But God,

being rich in mercy, because of the great love with which he loved us, even when we were dead

in our trespasses, made us alive together with Christ—by grace you have been saved…” (ESV,

Ephesians 2:3-5a) (emphasis mine)

12

There is an apparent contrast between the two situations, and that contrast sheds a bright light on the

differences between them. Comparison and contrast observations such as these can be a great tool in

the understanding of a biblical text.

Cause and Effect

“If this, then this.” Here is a classic example of a cause and effect. Biblical authors will generally describe

a situation and then explain it. Conjunctions such as “for,” “therefore,” and “then” usually connect them

together. Cause and effect will often times be depicted as a situation that happened, and the results of

that situation explained. Cause and effect can be in either past tense or future tense, depending on the

situation, and this should be taken into consideration when making cause and effect observations.

Causes and effects are sprinkled throughout the entirety of Scripture. Here is a great illustration of cause

and effect at its finest, found in the twelfth chapter of Romans:

“Do not be conformed to this world, but be transformed by the renewal of your mind, that by

testing you may discern what is the will of God, what is good and acceptable and perfect.” (ESV,

Romans 12:2)

The cause in this verse is the transformation by the renewal of the mind, with the effect being the

capability to discern the will of God.

Rhetorical Devices

The last part of speech that will be discussed is the rhetorical device. This is a rather advanced part of

speech, but it is worth noting that it plays into the text often. Some rhetorical devices include figures of

speech, idioms, analogies, metaphors, and similes. These devices have the potential to be noted and

studied deeper when going through the interpretation process, which will be explained in the next section.

Interpretation: The Foundation for Studying the Bible

The breakdown of communication between God and man as discussed above creates the need for

proper interpretation. Interpretation is the process focused on understanding what someone else is

saying. With the Bible, it refers to the search for the meaning of what the Scriptures are communicating.

When searching for meaning, it is important to look for what makes the most sense. Gordon Fee and

Douglas Stuart assert that “the aim of good interpretation is simple: to get at the ‘plain meaning of the

text’” (Fee, Stuart 18). Common sense should be the key ingredient when looking at the Word of God, or

else absurd, unbiblical ideas will be read into the text. A good interpretation has been reached when it

brings “relief to the mind, and a prick or prod to the heart” (Fee, Stuart 18).

The Journey of Interpretation

As one begins to look into the Word of God, it is crucial to note that we do not create the meaning of the

text; rather, our goal is to find the meaning that is already present and waiting to be unpacked (Duvall,

Hays 21). Isn’t it great that the God of the Bible is the one who desires to be sought out? “It is the glory of

God to hide a matter, but the glory of kings to search it out” (ESV, Prov. 25:2).

When first approaching Scripture, it is important to realize that the original words spoken and the cultural

situation in which they were spoken are not the same as they are today. Studying the Bible is similar to

studying any kind of history, with the goal moving from history to present understanding.

Yet nothing in the Word of God is to be ignored, including difficult passages. The interpretive gap exists

between when it was written and now when it is being read. J. Scott Duvall and J. Daniel Hays, in their

book Grasping God’s Word, brilliantly define how to understand the interpretive gap between the past

world of the Bible and the present:

13

“Many texts in the Bible are specific, concrete, revelatory expressions of broader, universal

realities or theological principles. While the specifics of a particular passage may only apply to

the particular situation in the biblical audience, the theological principles revealed in that text are

applicable to all of God’s people at all times” (Duvall 21).

The authors of the Bible had a purpose in writing each book as the Holy Spirit inspired them. The job of

students of the Word of God is to seek to find the meaning God intended. In order to do this properly and

effectively, there are four interpretive steps to this process taken from Duvall and Hays.

1

—————

Step 1: Grasping the Text in Their Town

Question: What did the text mean to the biblical audience?

This first step is to read the text and figure out as much as you can about what is happening in that

passage.. The discoveries are to be specific, as this is the bedrock for interpretation. As was stated

earlier, the biblical authors had intent when writing, and the aim in this step is to figure out what that intent

was. The history behind that passage and book of the Bible is critical to grasping the text in their world.

In the end, try to come up with one or two sentences of the meaning of that passage to the biblical author:

God commanded Moses in Exodus 3 to . . .

Paul exhorted the Philippians to . . .

Jesus taught the crowds by . . .

Just remember that principles are not trying to be formed at this stage — just simply the meaning of the

passage as it related to the original author. (Duvall, Hays 22)

Step 2: Measuring the Width of the River to Cross

Question: What are the differences between the world or the biblical audience and that of the modern

reader?

There are many things in today’s age that separate us from the biblical authors. These include the

language, culture, situation, time, and covenant.

2

The combination of these things results in a type of

“barrier” that must be crossed in order to understand the passage. However, the width of the barrier is not

the same with every passage. Sometimes, the area of differences is very wide, requiring a long, large

bridge of principles, while other times it is so narrow we can merely hop over. This is why it is important

to determine how wide it is with each passage that is being studied. Step 2 requires looking at the

difference between the situation then and the current situation. (Duvall, Hays 22-23)

Step 3: Crossing the Principle Bridge

Question: What is the theological principle or spiritual truths that relate to our day?

The point in this step is not to create the meaning, but rather, discover the meaning that the author

wanted to be found. God gives universal truths and teachings from His Word for all people of all ages to

learn from. In this step, the goal is to search for those timeless truths. The truths discovered are not going

to be applicable for only one group of people in one specific time, but they are pertinent for all

generations.

1

The steps and initial questions are taken directly from Grasping God’s Word — (Duvall, J. Scott., and J. Daniel Hays. Grasping

God's Word: A Hands-On Approach to Reading, Interpreting, and Applying the Bible. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2001. Print.),

and the content is derived from it as well. For a more detailed description of each step, see pages 22 through 25 of Grasping God’s

Word.

2

This concept will not be covered, for it presents a more advanced situation with which we must struggle to understand.

14

To go about discovering the truths and principles from the text, the first thing to do is to review the

differences from Step 2, and then look for the similarities between then and now. Once that’s been done,

the key is to identify a theological principle that is reflected in the text — one that relates to the similarities

between the biblical audience and us. This is our “principlizing bridge” that helps us cross the “river of

barriers” (Duvall, Hays 23) such as culture and time.

Theological principles should be formed under the criteria as stated by Duvall and Hays:

The principle should be seen in the text.

The principle should be timeless and not tied to a specific situation.

The principle should not be culturally bound.

The principle should correspond to the teaching of the rest of Scripture.

The principle should be relevant to both the biblical and the contemporary audience. (Duvall 24)

Step 4: Grasping the Text in Our Town

Question: How should individual Christians today apply the theological principle from the text?

This final step is applying the theological principle to the world here and now. The question to ask is

“What’s the point? How does this apply to everyday life?” Even if there is only one or two theological

principles from a passage, there might be many applications for the believer today. The principle may be

applied in different ways to different life situations, but the principle will remain the same. (Duvall 24-25)

—————

These four steps are incredibly beneficial when looking to interpret what Scripture is saying, and how it

applies to everyday life. This type of study helps bridge the gap between God’s Word and modern

understanding. It may take some extra thought, but the result is very rewarding.

To Sum It All Up…

The Bible is a magnificent story to be unfolded, filled with vivid pictures of the love of God toward

humanity. How lucky it is to have a God that desires to be close, and who deliberately speaks through the

Scriptures! The Bible is the most important book anyone could ever lay hands on, and because of this, its

stories, instructions, and lessons should be taken very seriously. The approach to Scripture should

always be in an attitude to learn, as the Holy Spirit will meet us right at the start. There are many steps

the believer can take to understand the Word of God, and as long as there is a surrendered heart to the

Lord, the Scriptures will come alive.

“All Scripture is God-breathed and is useful for teaching, rebuking, correcting and training in

righteousness, so that the servant of God may be thoroughly equipped for every good work.”

(New International Version, II Timothy 3:16-17)

Further Reading Recommendations:

The Journey from Texts to Translations: The Origin and Development of the Bible

by Paul D. Wegner

Canon Revisited: Establishing the Origins and Authority of the New Testament Books

by Michael J. Kruger

Can We Still Believe the Bible?: An Evangelical Engagement with Contemporary Evangelical

Engagement with Contemporary Questions

by Craig Blomberg

15

Methodical Bible Study

by Robert A. Traina

How to Read the Bible Book by Book: A Guided Tour

by Gordon D. Fee and Douglas Stuart

How to Read the Bible for All Its Worth

by Gordon D. Fee and Douglas Stuart

Grasping God's Word: A Hands-On Approach to Reading, Interpreting, and Applying the Bible

by J. Scott Duvall and J. Daniel Hays

Systematic Theology

by Wayne Grudem

Christian Theology

by Millard J. Erickson

16

Exercise #1

In this exercise, make note of the parts of speech and literary techniques Paul used in Romans 12. This

exercise is one of observation, acknowledging various pieces of the text that will contribute to the

understanding of the passage as a whole.

Therefore, I urge you, brothers and sisters, in view of God’s mercy, to offer your bodies as a living

sacrifice, holy and pleasing to God—this is your true and proper worship. Do not conform to the

pattern of this world, but be transformed by the renewing of your mind. Then you will be able to

test and approve what God’s will is—his good, pleasing and perfect will.

(New International Version, Romans 12:1-2)

Exercise #2

This exercise will be to put the Interpretive Journey into practice. Ask each of the four questions

3

while

going through this passage, and write them out on a separate sheet of paper.

“

42

And when the Philistine looked and saw David, he disdained him, for he was but a youth, ruddy

and handsome in appearance.

43

And the Philistine said to David, “Am I a dog, that you come to

me with sticks?” And the Philistine cursed David by his gods.

44

The Philistine said to David,

“Come to me, and I will give your flesh to the birds of the air and to the beasts of the field.”

45

Then David said to the Philistine, “You come to me with a sword and with a spear and with a

javelin, but I come to you in the name of the Lord of hosts, the God of the armies of Israel, whom

you have defied.

46

This day the Lord will deliver you into my hand, and I will strike you down and

cut off your head. And I will give the dead bodies of the host of the Philistines this day to the birds

of the air and to the wild beasts of the earth, that all the earth may know that there is a God in

Israel,

47

and that all this assembly may know that the Lord saves not with sword and spear. For

the battle is the Lord’s, and he will give you into our hand.”

48

When the Philistine arose and came and drew near to meet David, David ran quickly toward

the battle line to meet the Philistine.

49

And David put his hand in his bag and took out a stone and

slung it and struck the Philistine on his forehead. The stone sank into his forehead, and he fell on

his face to the ground.”

(ESV, I Samuel 17:42-49)

Step 1: What did the text mean to the biblical audience?

Step 2: What are the differences between the biblical audience and us?

Step 3: What is the theological principle in this text?

Step 4: How should individual Christians today apply the theological principle in their lives?

3

These questions are taken directly from Grasping God’s Word — (Duvall, J. Scott., and J. Daniel Hays. Grasping God's Word: A

Hands-On Approach to Reading, Interpreting, and Applying the Bible. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2001. Print.)

17

WORKs CITED

Duvall, J. Scott., and J. Daniel Hays. Grasping God's Word: A Hands-On Approach to Reading,

Interpreting, and Applying the Bible. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2001. Print.

ESV Study Bible: English Standard Version. Wheaton, IL: Crossway Bibles, 2010. Print.

Fee, Gordon D., and Douglas K. Stuart. How to Read the Bible for All Its Worth. Third ed. Grand Rapids,

MI: Zondervan, 2003. Print.

Malmin, Kenneth P. Bible Research. Portland, Or.: City Christian, 1990. Print.

The Holy Bible: New International Version. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2005. Print.

Sproul, R. C. Knowing Scripture. Downers Grove, IL: Inter Varsity, 1977. Print.